The post-riot analysis and argument continues to flow with a number of contributions focusing on youth work itself.

Rachel Williams in the Guardian interviews young people on the streets of Kings Lynn in Norfolk.

Teens are left to their own devices as council axes all youth services

On his blog there is a thought-provoking piece from Paul Perkins, CEO of the Winch project in Camden, which asks,

How did youth work contribute to the riots?

I can’t say I’m convinced by the assertion that occupying ‘the grey middle, which common sense tells us will always yield a more holistic truth than can be found at the extremes.’ Leave my extremist perspective aside Paul poses some tough dilemmas, immediately recognisable by those involved in our Campaign.

But it seems that youth work, somewhere along the way, lost its soul. As supply outstripped demand for serious youth work jobs, hundreds of short-term, part-time, state-led initiatives sprung up all over the place. Youth workers were a dime a dozen, and a sort of lowest-common-denominator youth work emerged. Perhaps the discipline simply struggled to move forward, to understand itself outside radical Leftism when society and policy changed. New Labour policies and the subjugation of youthwork to state surveillance and economic unit production activities (a question which was hotly debated in the 1980s and before) further confused a professionally naive workforce intent on securing funding and maintaining activities regardless of cost. Mixed in with the political cocktail of quick-fix solutions and sexy numbers, many parts of the sector has seen a near-complete loss of professional integrity over the past ten years. Let me be clear: this is not a dig at one government. I have no doubt that youth work would have been seen and utilised in the same way regardless of the colour of government. This is about the hard place which youth workers occupy, between the hardest-to-reach young people and a wider society impatient for peace.

Let me give an example. Most youth workers understand that, whilst there must always remain a drive to improve effectiveness and efficiency, the nuts and bolts of our trade are fairly common sense. Long-term relationships beat short-term relationships. Young-person-centred conversations beat funder-stipulated-conversations. Community-based initiatives trump centralised or super-centre initiatives. And this is in relation to impact: to making the difference which whether you’re a neighbour, a funder, a councillor or a youthworker, we all agree on.

But we have not maintained these working practices. There is pressure to bring young people in through the door (even if they’d rather meet outside). There is pressure to record their behavioural changes (with their token endorsements). There is pressure to gain them ‘qualifications’, whether or not these are meaningful in the employment market or are what they really want to do. And this has led to incentivisation, increasingly coercive approaches to engaging young people and undermining the core values of informal education which lead to an individual voluntarily, responsibly and productively choosing to engage with mainstream society and to be bound by its (mutually beneficial) social norms. To paraphrase, youth work has increasingly been guilty of encouraging young people to engage for what they can get, rather than investing in the best ways to inspire personal growth and civic responsibility.

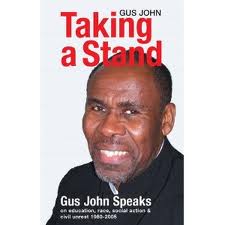

I’ve only just discovered this Open Letter to the Prime Minister written by Gus John, which begins,

I write as someone whose contribution for more than four decades to the struggle for quality schooling and education for all and for racial equality and social justice is a matter of public record. I write as a former youth and community worker, community development officer and director of education and leisure services whose work has been predominantly in urban settings. I am a social analyst and professor of education. I am interim chair of Parents and Students Empowerment, an offshoot of the Communities Empowerment Network which for the last twelve years has been providing advice, guidance and advocacy in respect of the one thousand (1,000) school exclusion cases on average we deal with each year.

It is a powerful and comprehensive critique, which deserves all our attention. As to whether David Cameron will give it the time of day, I won’t hold my breath.